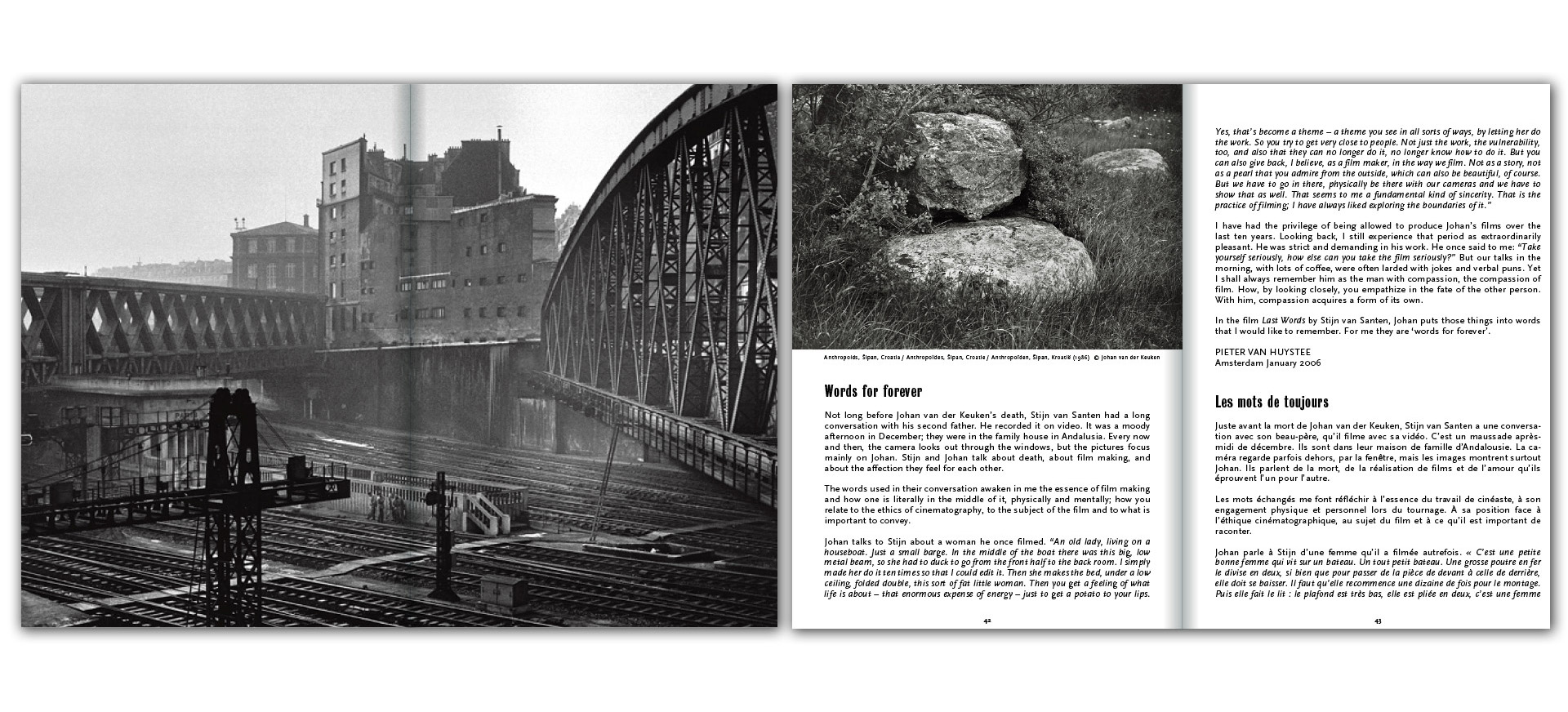

<div center;"=""> After earlier comparing the manner of composing a film to a game of cards, this is a paroxysm: everything is possible, any image can follow on from another (collage), the camera can go where it pleases. But the game is not gratuitous, physical exercise is not a stylistic composition: the whirling camera is still in confrontation. In the beginning, as we said, the filmmaker confronts himself, boxes with himself, aims blows that he avoids in the reverse shot, ripostes, then affronts things and beings with “a loaded camera”. Place de la République in Paris, a poster, a newsstand, a black passer-by, the increasingly speedy bonds that the camera tracks, hand-held, encouraged by frenetic movement to spin from one to the other. Later, in Sarajevo, the façade of a building that was the target of nationalistic battles, its gaping windows, its coloured concrete surfaces, a patchwork of devastation, a vestige of the paintings by Paul Klee, with little squares of colour, that the filmmaker liked so much.